Cambodia : From Democracy To Outright Dictatorship

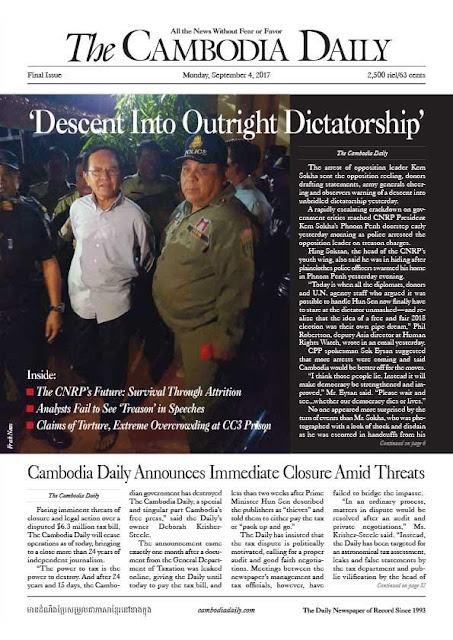

On September 4, the final edition of Cambodia’s oldest English-language daily rolled off the presses. The Cambodia Daily, founded in 1993, was a respected pillar of the country’s small independent media. True to its slogan—“All the News Without Fear or Favor”—the newspaper had forged a reputation for meticulous reporting and hard-hitting exposes. A month earlier, the Cambodian government, under the long-ruling Prime Minister Hun Sen, had hit the paper's publishers with a $6.3 million tax bill, ordering them to pay up or “pack up.” Such astronomical tax bill made sure that they will have to take the latter one.

“We have been a burr in Hun Sen’s side for the entire time that we have been operating,” said the newspaper’s American editor-in-chief, Jodie DeJonge.

“This paper takes special pride in writing about some of the toughest issues,” she said as office workers packed belongings into cardboard boxes.

Hun Sen defended the deadline given to the paper, saying it had to pay tax the same as any other business.

“When they didn’t pay and we asked them to leave the country, they said we are a dictatorship,” he said.

The paper’s last day coincided with the arrest of the Cambodian opposition leader, Kem Sokha—an incident that made the front cover of the Daily’s final issue. Kem Sokha,who heads the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), has since been moved to a remote prison in eastern Cambodia. He faces 15–30 years in prison and has been

charged with treason for conspiring with the United States to overthrow the Cambodian government.

As evidence, the authorities produced a video of Kem Sokha giving a talk in Australia in 2013, in which he describes meeting overseas experts “hired by the Americans in order to advise me on the strategy to change the leaders.” This, the government claimed, was proof of a conspiracy aimed at delivering a coup.

The closure of the Daily and the arrest of Kem Sokha represent unprecedented steps for Hun Sen, who has ruled in various guises since 1985.

Periods of repression are a regular feature of Cambodian political life and have occurred periodically over the past quarter century, usually ahead of elections.

It is also striking in that it has been accompanied by a sharp turn against the United States. Over the past year, Cambodia has pulled out of Angkor Sentinel, an annual bilateral military exercise, and kicked out a U.S. naval engineering battalion that was building school bathrooms and maternity wards in rural Cambodia. Following last month’s claims of a U.S. plot against the government, it silenced local radio stations relaying broadcasts from the U.S.-funded Voice of America and Radio Free Asia and ordered the closure of the National Democratic Institute (NDI), a U.S.-funded pro-democracy nongovernmental organization, which has been working in Cambodia since 1992.

According to most observers of Cambodian politics, the proximate cause of Hun Sen’s crackdown is the national elections scheduled for July 2018. The CPP is bent on avoiding a repeat of the last election in 2013, when the CNRP scored surprise gains on the back of rising public discontent related to land issues, corruption, and clotted government institutions.

The irony of Cambodia’s shift is that even as its democratic experiment ends, the pressure for change is building. The 2013 election was accompanied by massive public demonstrations of support for the CNRP from people who were tired of the outrageous levels of corruption and cronyism that have flourished under Hun Sen’s rule. That combined with recent deeds committed by Cambodian leader are surely going to reflect in 2018 elections.

|

| Final front page of The Cambodia Daily |

“This paper takes special pride in writing about some of the toughest issues,” she said as office workers packed belongings into cardboard boxes.

Hun Sen defended the deadline given to the paper, saying it had to pay tax the same as any other business.

“When they didn’t pay and we asked them to leave the country, they said we are a dictatorship,” he said.

The paper’s last day coincided with the arrest of the Cambodian opposition leader, Kem Sokha—an incident that made the front cover of the Daily’s final issue. Kem Sokha,who heads the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), has since been moved to a remote prison in eastern Cambodia. He faces 15–30 years in prison and has been

charged with treason for conspiring with the United States to overthrow the Cambodian government.

As evidence, the authorities produced a video of Kem Sokha giving a talk in Australia in 2013, in which he describes meeting overseas experts “hired by the Americans in order to advise me on the strategy to change the leaders.” This, the government claimed, was proof of a conspiracy aimed at delivering a coup.

|

| Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen casting his ballot |

Periods of repression are a regular feature of Cambodian political life and have occurred periodically over the past quarter century, usually ahead of elections.

It is also striking in that it has been accompanied by a sharp turn against the United States. Over the past year, Cambodia has pulled out of Angkor Sentinel, an annual bilateral military exercise, and kicked out a U.S. naval engineering battalion that was building school bathrooms and maternity wards in rural Cambodia. Following last month’s claims of a U.S. plot against the government, it silenced local radio stations relaying broadcasts from the U.S.-funded Voice of America and Radio Free Asia and ordered the closure of the National Democratic Institute (NDI), a U.S.-funded pro-democracy nongovernmental organization, which has been working in Cambodia since 1992.

According to most observers of Cambodian politics, the proximate cause of Hun Sen’s crackdown is the national elections scheduled for July 2018. The CPP is bent on avoiding a repeat of the last election in 2013, when the CNRP scored surprise gains on the back of rising public discontent related to land issues, corruption, and clotted government institutions.

The irony of Cambodia’s shift is that even as its democratic experiment ends, the pressure for change is building. The 2013 election was accompanied by massive public demonstrations of support for the CNRP from people who were tired of the outrageous levels of corruption and cronyism that have flourished under Hun Sen’s rule. That combined with recent deeds committed by Cambodian leader are surely going to reflect in 2018 elections.

Comments

Post a Comment